An increasingly popular argument put forth against Irresistible Grace (IG) is the so-called “love potion” analogy. The first time I heard it used was from Leighton Flowers a couple years ago, but I’m uncertain if it originated with him. My guess is that it’s existed in one form or another for a long time. Anyway, upon first hearing it, I was somewhat puzzled why it holds sway with people. It seems obviously flawed, so much so that I’ve had a hard time getting motivated to answer it. Yet many do in fact view this analogy as a persuasive argument against IG, and I’ve run into it in discussions more than once. My intention in this brief post is to assess the “love potion” analogy and give clear reasons why it doesn’t work, and also offer a better analogy to IG, that of an antidote.

My summation of the Love Potion Analogy:

A young man desires a girl’s affections. But she isn’t willing, and has no interest in this guy. The man comes upon a potion that can cause anyone, even the most unwilling woman, to fall immediately in love with him. So he finds a way to slip some of the potion into her drink. Soon afterward she finds herself liking this guy, and is now willing to go out with him.

Most would agree that this is unethical. It brings to mind certain “date drugs” wherein a woman is made to have lower inhibitions, and barely conscious enough to be in any sense a truly willing participant. In fact, drugging someone like this and then using them is rightly classified as rape. In a similar fashion, if the woman is drugged into a romantic relationship with the man, the same classification would be in order.

Some non-Calvinists (NC) see in the analogy a great example against IG. If God internally changes the heart of someone who hates him, this is likened to spiritual rape. Like the woman, the person didn’t ask for a heart change. Likewise, just because someone is now willing isn’t truly meaningful, since the process to get there involved spiritual force, no different than if they were given a drug. If God has to force someone to love him, this isn’t true love. Does this reasoning hold?

Before answering the charge, let’s extend the analogy out a bit:

After some time God changes the heart of the man so he loves God and feels very sorry for what he did to the woman. He confesses what he did to her and gives her the antidote potion, which she takes somewhat reluctantly, but willingly. Soon after, she finds she no longer wants to be with the man, and moves on.

Based on the above reasoning from the NC, God’s intervention in this way is equally as problematic as what the man did. Why? Because in both cases an unwilling participant was forced to become willing in order to achieve an end goal. Yes, the woman was now free – a net positive for sure – but the man’s will was violated, which isn’t good. A NC might answer that the man, like Pharaoh, gave up his rights to be treated nicely. Instead of hardening, he was softened. But this is special pleading. We’ve all rebelled and could be considered candidates for a heart change. Why limit it to the man? Further, such an argument gives tacit approval to God being in the right to actually perform such an act on an unwilling, sinful individual. It’s doubtful a NC would want to go down this path of rebuttal.

Two core arguments and a better alternative

So let’s get into some of the primary problems with the Love Potion Analogy.

First, we should recognize the difference between an action that is beneficial and right, versus one that is born out of impure desires. This has to do with the “intervener” and his motives.

Second, a distinction needs to be placed between a condition needing remedied, and one that does not. For instance, a doctor wouldn’t remove a healthy arm, but might need to if cancer or infection makes it life-saving procedure. This has to do with the “condition” of the individual, if they have one.

Let’s consider an alternate analogy: the antidote scenario. I’ll argue that this better fits what’s meant by IG.

A scientist illegally creates a new variety of poisonous spider through genetic engineering. One of these spiders bites the scientist and he becomes a different person. If he was rebellious before, he is now much more so. He plots to unleash the spiders into the population, an act that would ruin untold lives. A fellow scientist creates an antidote and she offers it to the first scientist. He refuses it and is upset that she has created it. With no time to waste, the second scientist sneaks into the first scientists room while he is sleeping, and jabs the antidote into his arm. Within a matter of hours he begins to come back around to where he was before. Realizing what has happened, he destroys the spiders.

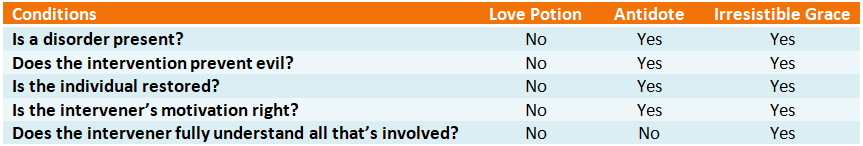

Most would agree with the actions of the second scientist. The first scientist was a real and present danger to himself and many others. He became a much different man than before. The question as it pertains to the present discussion is this: Was this a moral act to give him an antidote against his will, in order to effectively change his will? Though she doesn’t fully understand all of the ramifications, the antidote will efficiently put him back to a more normal state, where his will is governed by his previous nature. While that nature wasn’t perfect by any means, it was preferable to the one that made him willing to kill with impunity. This isn’t an exact parallel to what I’m saying God does in IG, but it is close enough to help us see the distinction between an antidote and a love potion. It might be helpful to visualize this in chart form:

As shown, IG is much closer by analogy to an antidote or a medicine than it is to a love potion. It should be obvious by now how flawed the love potion analogy is. But there is another aspect to consider, one that most Christians throughout the ages have agreed upon, and which should put the final nail in the coffin.

God’s rights over life and death

It’s unwise to arbitrarily compare man’s actions against man with God’s actions against man. We should accept, for instance, that God has authority over life and death. He indisputably gave us this life, and he also has complete rights to remove this life as he sees fit. Mankind has no rights to create human life, and very strict limits on taking human life. In that light, let’s redo the analogy:

A man sees a young woman he likes. But she consistently resists his advances. Because he can’t stand the thought of her being with anyone else, he goes to her home and kills her.

Of course we all recoil in horror at such a crime. But what if someone uses this to argue that it would also be wrong for God to take a life? In point of fact, there are some who do, though more often than not they’re non-Christian skeptics. I’m not here arguing that God just “can’t stand” the thought of people not loving him, so he then kills them. No, God is incredibly patient with blasphemous rebels, which is ample proof that he doesn’t act on emotions or flawed thinking as we humans do. My point is that both Calvinists and non-Calvinists would object to the skeptic’s analogy and would answer it in a like manner. Perhaps those who use the “love potion” analogy should step back and consider if they’re using this illustration just as wrongly.

Summary

I’ve attempted to make it clear that Irresistible Grace bears little resemblance to the “love potion” analogy. God is correcting a disorder, a moral inability characterized by extreme self-centeredness and lack of love toward God. While it’s true that nobody asks to receive God’s grace – at least apart from that same grace – this is to be expected. Why would they ask for that which they don’t want? A marred will won’t choose its way out of a predicament it doesn’t even recognize. No, our wills aren’t violated by IG; rather, our nature is restored enough so that our wills are able to freely love the gospel of Christ. God’s intervention corrects a corruption, not unlike how LASIK corrects myopia, or a cochlear implant restores hearing. Likewise, once we see and hear clearly, we are set free to freely love God; whereas previously, our perception of him was degraded, so that this love wasn’t even possible.

Let us not forget that God made us, knit us together, determined the time we would live in, the nation we would inhabit, and the family we would have to influence us. He constructed both body and spirit, knowing the interplay between the two and how this newly created person would react in that environment. Both our nature and nurture are in his hands. In his perfect knowledge and vast wisdom, God knows precisely what each individual needs in order to believe. His motives, as in all things, are pure. How is it considered negative when we pass from certain eternal death to eternal life? In summary, while there is a surface-level similarity between a “love potion” and Irresistible Grace, the analogy falls apart upon closer examination.